Recreation and Risk is published by Carolina Academic Press, and it’s available now. They’ve been great to work with, and I’m excited to make tens and tens of dollars.

Click here for CAP’s page for the book, where you can order it; if you are a professor and want to request a review copy, there’s a link there. You can also order it from Amazon. Unfortunately, it’s not available via Bookshop or the like. Buying it direct from CAP is usually no more expensive—and sometimes cheaper—than Amazon.

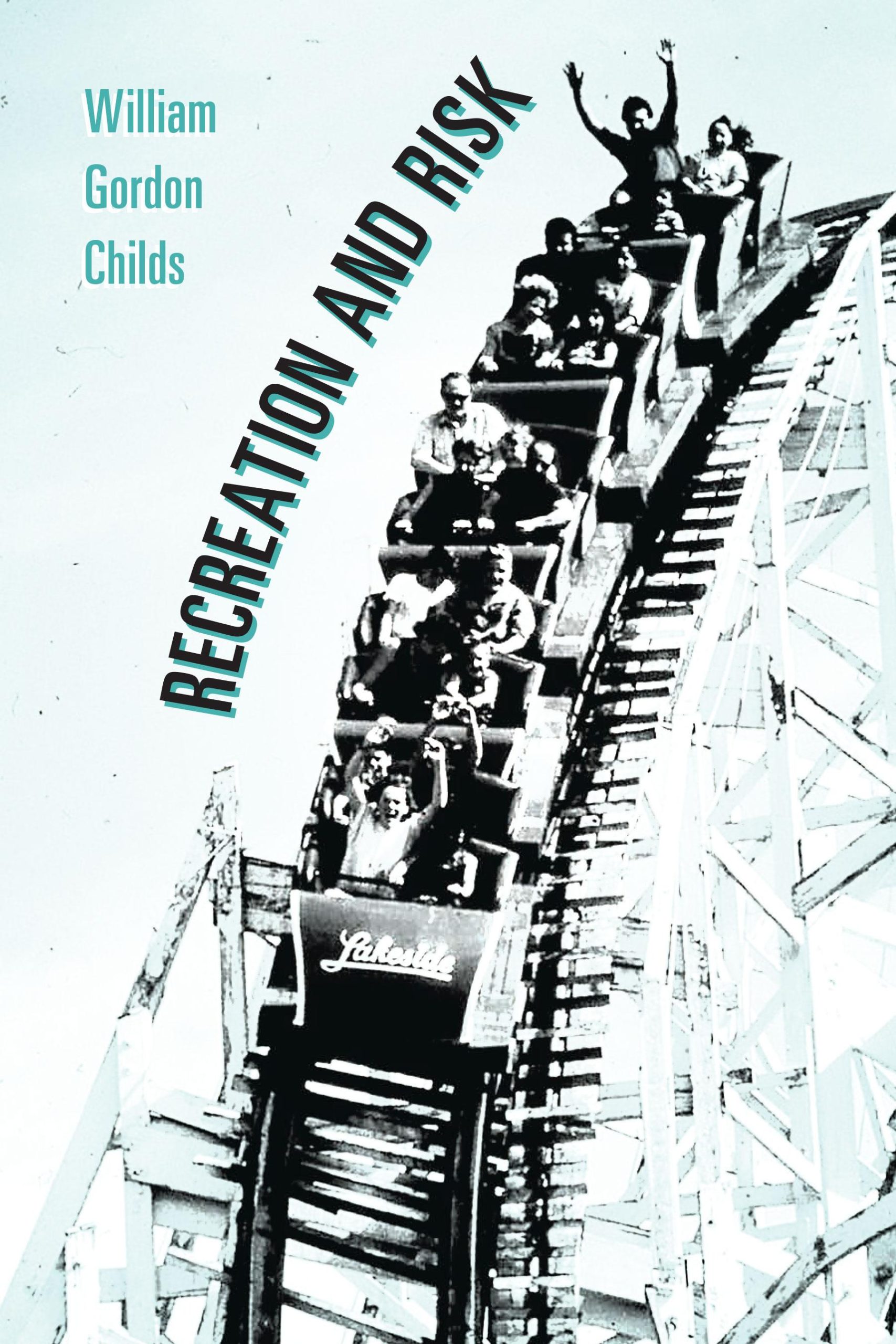

Here’s the cover, which I love.

Photo courtesy of National Amusement Park Historical Association Archives, John M. Caruthers Collection.

And here’s most of the Author’s Note (current draft):

“Do you know what that means, to be in the amusement business?”

“No, sir, not exactly.”

His eyes were solemn, but there was a ghost of a grin on his mouth. “It means the rubes have to leave with smiles on their faces…[T]he place turns ’em into rubes with their mouths hung open. If it doesn’t, it’s not doing its job…. [They] have to leave happy, or this place dries up and blows away. I’ve seen it happen, and when it does, it happens fast.”

Stephen King, Joyland (2013)

Most rides and attractions are designed to make you feel like you’re in danger—that’s why you get that adrenaline rush—without, you usually assume, endangering you. Get on a roller coaster, go into a haunted house, or board a drop ride: Do any of these, and you generally expect to get through the experience with a thrill and nothing else more unpleasant than maybe a bump or a bruise.

This casebook is about the case law, statutory provisions, and regulatory structures related to that core idea and what happens when that expectation is not met.

Amusement parks and carnivals sit at intersections that make them particularly interesting legally. Fixed-site parks’ rides aren’t regulated by the federal government, leaving them to a patchwork of state regulations; carnivals are—kind of—federally regulated, but also fall under state rules. Questions of assumption of risk and comparative fault are complicated when the idea of the attraction is to make you feel simultaneously in danger but also in a bubble of assumed safety. The contractual questions raised by waivers purporting to limit liability are complex. And so on.

This casebook grew out of a course I created framed by New Jersey’s Action Park, and Action Park will appear throughout it. Action Park upended most of the assumptions about amusement parks. It generated thousands of stories (many of them true), countless injuries, a number of deaths—and at least 100 lawsuits. At its peak in the 1980s and 1990s, it was wildly popular with kids on the east coast for many of the reasons it was also far more dangerous than more conventional parks—the guests had a great deal of control over their experiences, and, thus, their risks. The risks that were illusions in most places were reality there.

My premise is that we can sometimes learn the most about the development of various areas of law by exploring situations in which someone pushes those areas’ boundaries. Accordingly, the book spends a lot of time on tort law, but also touches on administrative law, criminal law, the interplay of federal and state law and regulations, and insurance law.

The goal is to better understand the various ways that tort and other doctrinal law evaluates (and affects?) the conduct of actors—both plaintiffs and defendants—and to be better prepared to make arguments related to such topics, recognizing that conduct often arguably falls within more than one doctrinal approach.

Given the topic, the casebook includes some upsetting fact patterns. They are included not for shock value, but because they represent an opportunity to explore important issues. Keep in mind—as I do—that these are real people and real injuries. That said, I hope you find the case as much fun to take as I have found it to teach—I love amusement parks (my roller coaster count is around 200) and I love thinking about these issues.

In focusing primarily on one broadly-defined industry rather than one doctrinal area, this casebook is unusual. In doing so, it seeks to help you think about the range of legal issues that affect businesses. In practice, lawsuits don’t come in your door labeled with just one doctrine (“Hello, my name is Products Liability—Warnings Defect”). Whether you’re advising or defending a business or suing it, it’s necessary to recognize those cross-doctrine questions. Hopefully this will help.

Notwithstanding the somewhat uncommon subject matter, the casebook is broadly conventional in structure. However, because of the range of issues addressed, the chapters necessarily often touch on more than one topic, notwithstanding their relatively narrow titles. I have attempted to keep the notes focused and less voluminous than in some casebooks. I’ve also included a chapter with extensive (largely primary) materials from one (real and tragic) incident from the fall of 2021, to provide the opportunity for you to do an in-depth case study.

More than, I suspect, any other casebook you’ve used, you’ll see a lot of primary source materials (like investigation reports) and pleadings (as opposed to opinions). In the same way cases don’t come in the door labeled with a doctrine, they also don’t come in with all of the issues identified, and a lot of being a litigator in particular involves getting good at analyzing things like investigation reports.

Some of the book will feel like a refresher from other classes you’ve taken. From time to time, it may feel like it’s at odds with some of those classes. As you have no doubt already figured out, there’s more than one way to approach some key issues in the law, and certain subjects here are, I think, easier to understand with a particular approach. For example, I think primary assumption of risk is best thought of as a no-duty rule (as opposed to the more mundane defense some treat it as). Each approach has support in various cases and I won’t fuss about which approach is “right”—but for our purposes, the no-duty rule makes the most sense. Because not every Torts professor uses that approach, the book takes a bit of time to establish it.

Thank yous, academic division:

Professor Erin Buzuvis (for taking my idle “I could make this a class” as an offer to create and teach it at Western New England University School of Law); my former colleague Eric Gouvin (also at Western New England) for always being interested in what I’m up to; all the nice folks at Mitchell Hamline School of Law for making me feel welcome as an adjunct; South Carolina’s Professor emeritus David Owen (for pointing out that this would make a good casebook); Professor David Anderson and the late Professor David Robertson, both of the University of Texas School of Law (for helping me as a baby professor and for co-authoring my favorite Torts casebook). Thanks to all the great folks who have visited my class, sharing their wisdom and ideas, including director Seth Porges; Prof. Serena King; Judge Colette Routel; Zamperla Rides’ Adam Sandy; Ride Training International’s Erik Beard; Prof. Kathryn Woodcock; author Andy Mulvihill; activist Kathy Fackler; and attorney Elijah Watkins. And thanks, as always, to my students (especially Maggie Solis and Jasmine Campbell), both recent and more in the distant past, for enjoying, or at least putting up with, my ramblings about this stuff, and for asking great questions.

Thank yous, personal division: My family—my wife Dena and our (adult) kids Joss and Liam—for riding the rides with me and putting up with my ramblings about this stuff. Joss, who, despite being a scholar of early Christianity, is also obsessed with the National Transportation Safety Board Go Team and loves lengthy conversations about the appropriate model for regulations and investigations. And Liam goes to enough hardcore shows that I can learn about the accepted unwritten rules of the mosh pit from him, since I’m a few years out from being deep in the pit. Thanks also to my mom and late dad—Holly and Ves—for encouraging deep dives into obscure topics, even if they never really liked riding the rides, as far as I know. Also Christopher Churilla and Greg Van Gompel from the National Amusement Park Historical Association for their patience as we scrolled through hundreds of wonderful amusement park photos for the cover. On that note, I should add that the pictured coaster, the Lakeside Cyclone, has not had any significant accidents of which I am aware, and is on the cover because it’s beautiful, not because it’s risky. And, finally, Ana Marie Cox for her assistance in the editing process.

Dedication: To the memory of Professor Jon Western, who kept gently nudging me back towards teaching.

As I reference from time to time in the book, many materials related to this subject are available at RecreationAndRisk.com. I will try to post there from time to time as events warrant.

I hope you enjoy the book, and the course. Get in touch with any ideas. One of the weird delights of my specialty is former students reaching out every time something goes awry in an amusement park, and I’d be glad to add readers of this book to that list of correspondents. If you find yourself in Minnesota, get in touch and we’ll go ride some rides at Valleyfair or, if your timing is exquisite, the greatest state fair in the country.